A journalist friend on a Middle Eastern newspaper asked me about the 89th anniversary of the Balfour declaration. His paper is publishing a special supplement! He wondered how the anniversary was marked in Britain. The answer of course, is with bemused silence…why would we mark that anniversary year by year?

A journalist friend on a Middle Eastern newspaper asked me about the 89th anniversary of the Balfour declaration. His paper is publishing a special supplement! He wondered how the anniversary was marked in Britain. The answer of course, is with bemused silence…why would we mark that anniversary year by year?

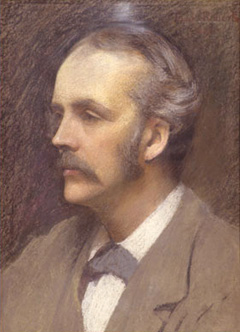

Arthur Balfour was a former British Prime Minister. In 1917 he was the Foreign Secretary and this was his declaration:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country”.

In the Middle East that paragraph, written on November 2nd that year, carries a historic resonance far beyond its impact here in the UK.

If Britons failed to notice the declaration, they had an excuse. 89 years ago, half a million Allied troops and 300,000 Germans were dying in the battle of Passchendaele. The British public and Britain’s army were consumed by war. And the deals and declarations of diplomats were as far removed from the general public then as they are today.

Today the Balfour declaration is merely an uncomfortable reminder of a time when Britain was still a global imperial power. Any similar pronouncement by the UK’s Foreign Secretary would hardly carry the force of the world’s largest navy, or the backing of its greatest empire.

And despite the paper commitment, when Britain did come to administer Palestine under the post-WW2 mandate it actually opposed mass Jewish immigration. People that the House of Commons condemned as Jewish terrorists killed British troops. If you think of forgotten anniversaries, not many people this year marked the 60th anniversary of the bombing of the King David Hotel where 92 people died, 28 of them Britons.

Anniversaries are entirely spurious ways of remembering the past – but they are also symbolic opportunities to remember shared suffering and shared joy. Sometimes they can even be a chance for reflection. And what we forget, or fail to notice, is often more important than our memories themselves.